No Place Home: Venezuelan Exodus Part One

A recent poll reveals 45% of Venezuelans intend to emigrate from their homeland amid worsening political and economic conditions. But their are growing consequences resulting from their exodus

President of Venezuela, Nicolás Maduro, is more isolated now than ever before. His nation is grappling with its worst economic conditions in decades since his predecessor Hugo Chávez came to power in 1998. Hyperinflation peaked in 2019 by a staggering 9,500%, leaving citizens with empty shelves as scarcity rose among the most basic goods. Massive unemployment levels and a decline in the nation’s oil production exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, helped to plunge 50% of Venezuela’s 28 million residents into poverty, according to a survey conducted in November of 2022.

Venezuela’s political situation is no different. In January of this year, Maduro was sworn in for his third consecutive six-year term in Caracas, dashing the hopes of millions who dreamt of brighter days for the South American homeland. Massive evidence of fraud was found throughout the election, leading nations that included the United States, members of the European Union, and several Latin American governments including former ally, Gustavo Petro of neighboring Colombia to publicly condemn the results, whilst demanding transparency from the Maduro regime. Not withstanding, Maduro responded by tightening his grip on power, and censoring opposition leaders like María Corina Machado, whose allies claimed was “kidnapped” shortly after the election for publicly denouncing the results and Maduro’s regime. U.S. sanctions were then swiftly reapplied in late January against Venezuela as well as an increase in the reward for “information leading to the arrest or conviction” of Maduro for drug trafficking charges.

The crises of the last decade have led to rising unemployment, diminishing wages, fuel shortages, electrical outages, rising violence and organized crime, and the rapid deterioration of the nation’s infrastructure and public services. These conditions have left the citizens of Venezuela with few other options but to flee the misery and desperation, and seek shelter elsewhere. In early August of 2024, Meganalisis, a survey and data analytics company based in Caracas found that “43% of respondents said they were considering leaving their homeland between now and the end of the year.”

A total of 7.7 million Venezuelans have fled the country since 2014. About 70% of them have relocated in Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and Chile, according to Amnesty International. Poverty, hunger, humanitarian concerns and human rights violations have all contributed to a series of forced mass migrations over the span of a quarter of a century since the country was subjected to the most severe economic collapse of the 21st century - a common fate of nations whose very stability depend upon the fluctuating boom and bust cycles of petrostate economies.

Those who are willing to take the risk to reach the United States, often transgress by way of the Darién Gap, a dangerous and remote jungle crossing that stretches across Panama’s southern province, and operated by criminal organizations like the Gulf Clan who rob and extort traveling migrants at will. Those who are not, and perhaps possess neither the means, resort to crossing the Venezuelan border west, into Colombia, where some three million currently reside. In 2021 Colombia approved Temporary Protective Status (PPT) for Venezuelan migrants, affording them a 10-year grant for work authorization and access to medical care. However, assimilation has been increasingly more difficult recently due to local prejudices, and a public services infrastructure that no longer seems to have the capacity to provide necessary services for the large influx of migrants seeping into now smaller rural communities.

In Peru, approximately 1.5 million Venezuelans have made their way south where the country offers migrants similar services but access is much more limited compared to their Colombian counterparts. Peru is also substantially more aggressive in their refoulement procedures, a policy that involves the deportation of asylum seekers or refugees back to their countries of origin where they’re at risk of facing harm or political retribution upon their return.

Ecuador for instance, housing almost 500,000 Venezuelan migrants, offers even less services as it suffers from its own economic slowdown amid a recent drop in financial liquidity and disruptions in oil production. One of nation’s most severe droughts in recent years has caused tremendous turmoil for its farmers and rural populations. The central government is also facing the rising threats of organized crime as the nation heads to the polls for next week’s presidential election. The government of Daniel Noboa has recently deployed the complete militarization of the western ports of Guayaquil where 90% of the nation’s cocaine is distributed from.

The importation of migrant crime has posed problems for host countries including the “northern neighbors” of Mexico and the United States. In South American countries where full employment is complicated by temporary status, and where public services for incoming migrants is inundated with volume as other local resources are exhausted, these migrants will often resort to crime as criminal organizations involved in the lucrative drug trade and human trafficking operations are becoming more prominent in countries like northern Colombia and the western regions of Ecuador. Migrants are also sought after for forced recruitment by these gangs because of their lack of registration with the state, and because of their transient status, reports of missing persons submitted by concerned family members go mostly unheard. According to Colombia’s Attorney General’s Office, almost 300 Venezuelan migrants are reportedly missing from forced disappearances, most of which occur at the hands of criminal organizations and Colombia’s violent rebel groups.

In 1984, an agreement called the Cartagena Declaration was adopted by delegates from 10 Latin American nations, essentially reaffirming the right of asylum to refugees from the region, ensuring the signatories to provide necessary services for those who are threatened by a variety of situations including poverty, civil conflict, displacement and food insecurity. Ironically, several of the signatories - in this case Venezuela - have failed to execute one of the more important clauses of the agreement, which if continues unresolved will seemingly have the veritable effect of perpetuating the migrant crisis that surrounding nations presently find themselves encumbered by.

This clause, within the Declaration states that all signatories are “To ensure that the Governments of the area make the necessary efforts to eradicate the causes of the refugee problem." The causes of these displacements will certainly not be resolved in the coming years, perhaps even the coming decades, for they are structural and cannot simply be remedied by sheer political will. But so long as the conditions for continued mass migration exist, the incentives will remain, and migrants will always place priority in the comfort of their own safety and immediate needs over the concern for the inconvenience over others.

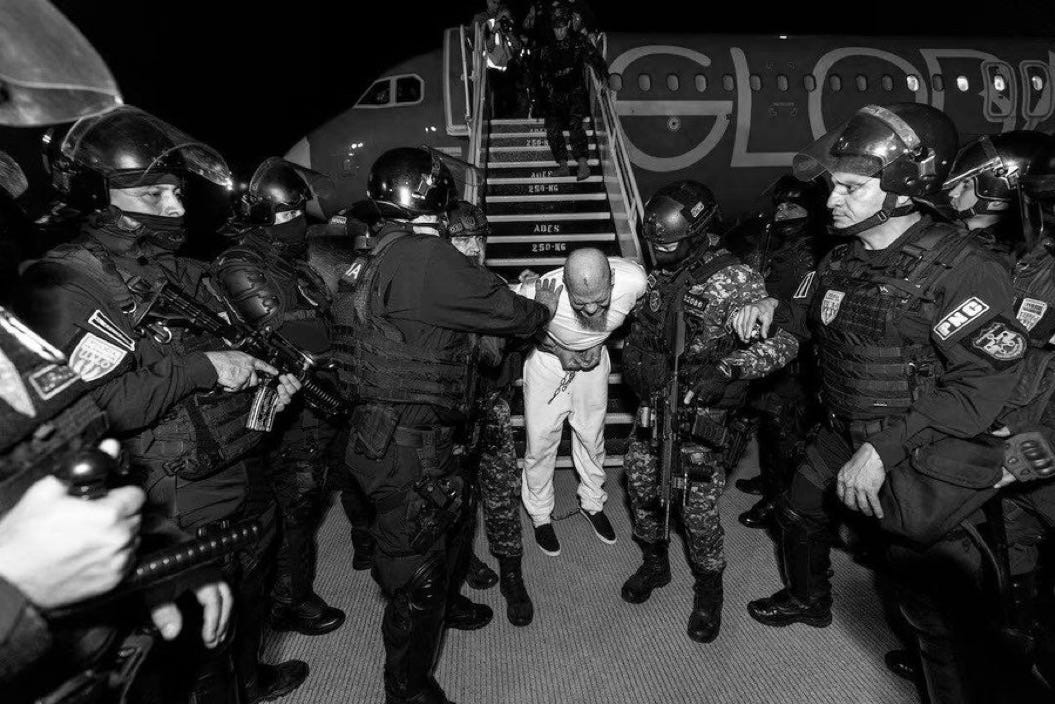

The proliferation of subaltern criminal organizations facilitating the growing drug trade in northern South America is also fueling the illegal movement of migrant individuals who are unscrupulously willing to take advantage of the rise in the criminal elements, not only in the regions in Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia, but also in the United States as well. Over one million Venezuelan migrants were encountered at the U.S. southern border during the Biden administration, thousands more are suspected members of the violent Venezuelan Tren de Aragua gang, who carved out pieces of territory and established footholds in some of the nation’s largest cities including Atlanta, Boston and Denver until U.S. ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) operations began carrying out removal proceedings. Tren de Aragua began to garner international attention when then candidate for the U.S. presidency Donald Trump, campaigned on the forcible removal of suspected gang members, and members of other organizations like the Salvadoran MS-13 from U.S. soil. In February, 2025, President Trump officially designated both groups as a Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO), and evoked the Alien Enemies Act of 1798 in order to expeditiously deport all violent criminal migrants and transferring their custody to Salvadoran authorities destined for that nation’s infamous Terrorist Confinement Center, also known as CECOT.

The Wilson Center produced a report on Migration & Human Development in July of 2023, pointing out that “Migration contributes to economic and human development by reducing global inequalities in the long term.” Undoubtedly, migration can alleviate unemployment strains for countries like Venezuela, whilst also reducing inflation as capital is removed from circulation. Venezuelan remittances from countries like the U.S. - from which $4.2 billion in 2023 were sent back home to family members who stayed behind - can also have a positive impact on local communities and individual lives in countries of origin. However, one must also ask what consequences are their for these countries of origin when millions of its residents suddenly decide to seek shelter elsewhere? Problems like population fatigue from losses of younger members of society, brain drain, and long-term stagnation in productivity can also arise from mass migration. Not to mention, those who are willing to flee with everything left behind are typically those who cause the most trouble for incumbent regimes, then only leaving those segments of the population who are willing to tolerant government abuses, strengthening the regimes rule over its own citizens. This is the vicious cycle of displacement and forced migration. There are only a few winners, and those who remain sometimes suffer.